Doing presentations as an Aboriginal author in several high school and university classes recently, I have found myself mentioning Sumer, the oldest written works currently known, and Inana, whose visit to her sister in the Underworld (a resurrection story), and whose expressions of appreciation for her own ladyparts (vulva in particular), have long held fascination for me. I have tended not to go into detail, just felt a need to bring the existence of these ancient poetries, the pre-monotheistic underlay of modern Iraq, and its powerful representation of female divinity, to the attention of the students, in the context of a conversation about Canadian indigenous people and modern literatures.

Doing presentations as an Aboriginal author in several high school and university classes recently, I have found myself mentioning Sumer, the oldest written works currently known, and Inana, whose visit to her sister in the Underworld (a resurrection story), and whose expressions of appreciation for her own ladyparts (vulva in particular), have long held fascination for me. I have tended not to go into detail, just felt a need to bring the existence of these ancient poetries, the pre-monotheistic underlay of modern Iraq, and its powerful representation of female divinity, to the attention of the students, in the context of a conversation about Canadian indigenous people and modern literatures.In the last year I've researched many things. Careful study by some scholars of the approach of Buddhism to Tibet—two distinct entities now fused in the popular mind, as a result of subsequent history and cultural evolutions, and embodied in the voice and person of the current Dalai Lama —and the use of feng shui geomantic studies to capture and direct the energies of the earth for a successful colonization. The story of the Supine Demoness, and other features of the landscape, and the careful use of architectural placement of temples to redirect the flow of qi by capture of the native energies, binding them into new forms of cultural life, is another old story with deep resonance, in turning our gaze back to the landscapes of Canada.

I have read, more than anything else, many essays about the 1001 Nights, from its translation into native Hawai'an newspapers (there used to be many) to the oldest extant roots of itself. I have not been reading the stories themselves, so much as examining what is known about the stories, where some are told still in oral form, who translated them when, how this became the representation of Middle Eastern aesthetics in the West, and how accurately representative Middle Eastern scholars might feel it to be. In particular I have been interested in the frame story, the tale of the storyteller as healer and political force.

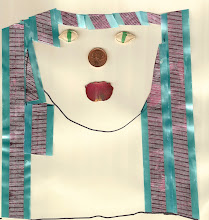

In recent months, cordel literature (string literature) of the Brazilian northeast, a living remnant of eurotraditions , the poor people's newspaper has been my focus: oral verse sung in markets, paper versions of the tales presented with woodcut illustrations and sold for a real. What current news and fantastic old tales are to be found in this living literature, how is this continuous tradition adapting to modern forms of both money-earning and the electronic circulation of poetic information.

, the poor people's newspaper has been my focus: oral verse sung in markets, paper versions of the tales presented with woodcut illustrations and sold for a real. What current news and fantastic old tales are to be found in this living literature, how is this continuous tradition adapting to modern forms of both money-earning and the electronic circulation of poetic information.

, the poor people's newspaper has been my focus: oral verse sung in markets, paper versions of the tales presented with woodcut illustrations and sold for a real. What current news and fantastic old tales are to be found in this living literature, how is this continuous tradition adapting to modern forms of both money-earning and the electronic circulation of poetic information.

, the poor people's newspaper has been my focus: oral verse sung in markets, paper versions of the tales presented with woodcut illustrations and sold for a real. What current news and fantastic old tales are to be found in this living literature, how is this continuous tradition adapting to modern forms of both money-earning and the electronic circulation of poetic information.If there is something that connects all of this, it is an imagined spectrum between the written on one hand and the oral on the other, and the experienced blend of the reality that exists between these points: and, a bisecting spectrum, the private uses of writing on the one hand, and the public uses of writing on the other, and all of the space between these, as well.

In the writing that I do, and that I like, the poet absorbs the world and attempts to put what has been absorbed back into the world: if you read this poem, if you listen with attention, if you open to receive it, then my experience may be carefully recreated within you, and that intimacy of samesame experience is our shared gift. Some call this perspective naive, marshal alternate conceptions of reality to argue against such human possibilities.

Stephen Owen, in writing about Chinese classical poetry for a western, modern, English-speaking audience, contrasts the “made world” of the west, where a God created the world and there it sits, and all the little creators upon it— artists of all kinds—make things, with the dynamic world of a Taoist perspective, in which each living being is a participant in a world creating itself, a dynamic being. Within this world, a living world, the making of a poem and the imbibing of the poet’s perspective is all very much a making, as opposed to a made thing: living interactions of worldmaking and ongoing creation.

Stephen Owen, in writing about Chinese classical poetry for a western, modern, English-speaking audience, contrasts the “made world” of the west, where a God created the world and there it sits, and all the little creators upon it— artists of all kinds—make things, with the dynamic world of a Taoist perspective, in which each living being is a participant in a world creating itself, a dynamic being. Within this world, a living world, the making of a poem and the imbibing of the poet’s perspective is all very much a making, as opposed to a made thing: living interactions of worldmaking and ongoing creation.We are all connected, a hum of living energies cascading through rock and water, voice and wind.

Joanne Arnott, 21 March 2009

Joanne Arnott is a poet and writer of Metis background, living and working in Richmond, British Columbia. Further parts of this essay will be posted at intervals on Schroedinger's Cat.

Illustrations:

Ishtar (Inanna) vase in the Louvre, photograph by Marie Lan-Nguyen/Wikipedia Commons

Wood engraving used to illustrate the cover of a cordel booklet

Image of Taoist poet and philosopher, Chuang Tsu